Dr. Akinwunmi Adesina helped transform how Nigerians think about agriculture, shifting it from a siloed, input-based activity to a system of interconnected value chains. Before his tenure as President of the African Development Bank, he served as one of Nigeria’s most influential ministers of agriculture. One of his major legacies was getting Nigerians to think about agriculture, not as an isolated, stand-alone activity requiring isolated solutions like periodic purchases of several thousand tons of fertiliser, but understanding agriculture as a series of ‘value chains’ that is, interconnected socio-economic systems involving multiple actors, resources and institutions.

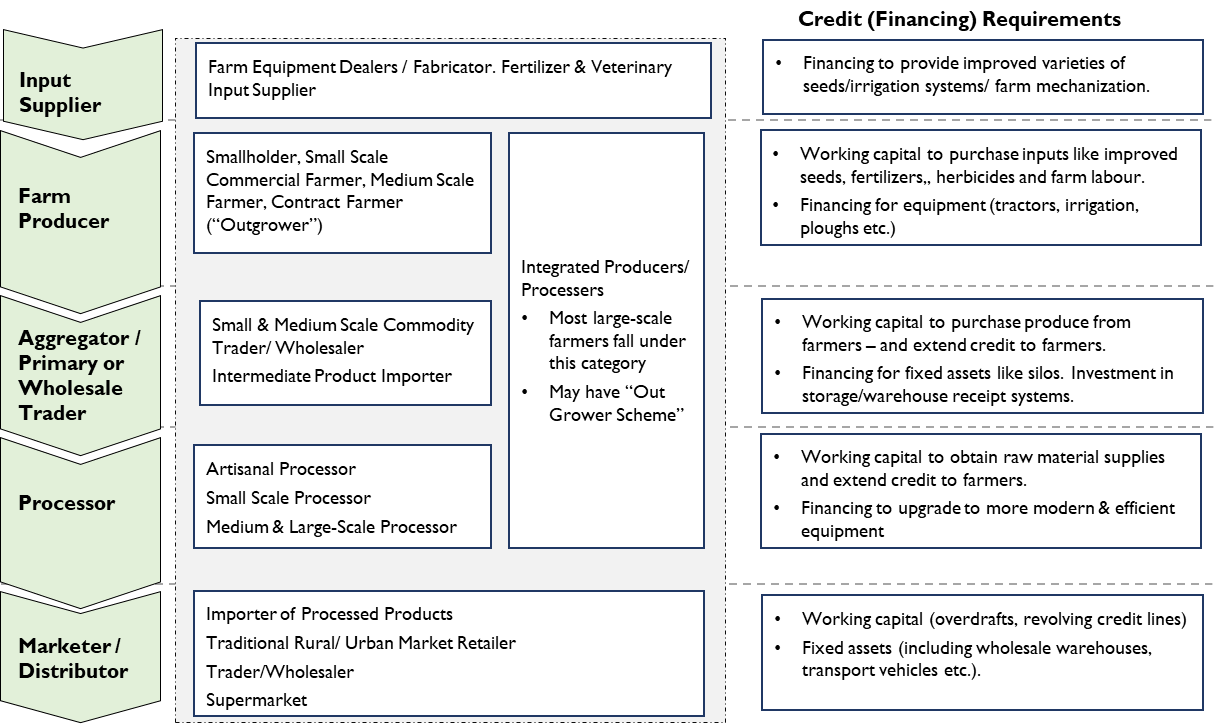

Value chains are, therefore, a useful frame of reference to understand the challenges, opportunities, constraints, and potential of agriculture in Nigeria. Illustrated in the following schematic and table is a generic value chain, along with a brief description of the main nodes in the agricultural value chain, which aids in understanding commonalities across major agricultural commodities.

Figure 1: Generic Agricultural Value Chain

Having identified the structure and key players in Nigeria’s agricultural value chain, the thrust of this study will be to critically examine key value chain challenges with a view to proposing solutions to these challenges.

High Input Costs

Foreign exchange fluctuations and persistently high inflation have led to the high costs of essential inputs, including fertilisers, seeds, labour, and animal/poultry feed. Consequently, cultivation costs have been on an upward trajectory, as illustrated in the following chart, which shows data (national averages) collated by the National Agricultural Extension and Research Liaison Services over five years.

According to data from NAERLS, there has been an 88.2% increase in the average cost of cultivating a hectare of cassava between 2019 and 2024. For maize and rice, based on this data, cultivation costs are estimated to have increased by 72% and 191.8% respectively.

Analysis of field data from specific projects reveals an even more dramatic increase over a four-year period. The data presented in the following chart and table show that while the cost of cultivating a hectare of cassava tubers was estimated at ₦270,550 in 2020, the costs per hectare in 2024 had ballooned to ₦825,180, representing a 205% increase in four years. Costs of inputs (cuttings, herbicides, fertilisers and labour accounted for the most dramatic increases (248.15% and 200.52% respectively.

Financing

Despite contributing 25.18% of Nigeria’s aggregate GDP in 2023, the banking sector's credit to the agricultural sector was approximately 5.5% of the total sectoral allocation of deposit money banks in the third quarter of 2023. This is illustrated in the following chart.

Above 90% of all agricultural activity in Nigeria is dominated by smallholder farmers (who typically cultivate 1–2-hectare-sized plots of land). Smallholder farmer financing needs are primarily driven by access to working capital for purchasing inputs such as seeds and fertilisers, paying for land preparation and cultivation activities, and securing loans to acquire equipment and other fixed assets.

As illustrated in the following chart, smallholder farmers experience cyclical cash flows and therefore require substantial working capital during planting and mid-season activities. This tends to leave them at the mercy of aggregators, who are the most willing to provide short-term financing, often on unfavourable terms to farmers.

Commercial banks should lend more to smallholder farmers, but the “financial intelligence of smallholder farmers” is a major impediment (this involves record-keeping skills, distinguishing between turnover and profit, etc.). Banks could identify and implement more innovative approaches towards lending to smallholder farmers, such as adopting the structure of village farming groups/using village group dynamics to structure financial products that cater to smallholders and mitigate loan risks.

More sophisticated value chain players, such as food processors, also face similar challenges.

- Poor record-keeping

- Lack of strategic understanding of the market and industry.

- Weak governance for business management.

- Inadequate skills to assess agricultural loans.

- Low entrepreneurial skill sets.

Banks are sceptical about investing in agriculture, but when they do, they are more interested in agricultural processing and marketing, rather than primary production. In addition, banks have a competence problem; most credit officers do not fully understand agricultural value chains.

High Interest Rates.

Commercial banks usually charge annual interest rates of MPR + a range of 2.5% to 5.5% (where the MPR is currently at 27.5%). However, borrowers also generally expect lower interest rates on their commercial loans due to the high operational costs associated with them. Most borrowers would like to have access to single-digit intervention fund loans from the Central Bank, but this is not always possible. Another major challenge is the ability of some intending borrowers to provide adequate or acceptable tangible collateral to secure their loan facility with the banks.

Low Productivity

Average yields per hectare for major food crops tend to be low compared to global averages. The charts below show the average yield (metric tons/hectare) for two essential commodities, tomato and rice. Results demonstrate that yields in Nigeria are significantly lower than yields in key benchmarked nations. Consequently, there is significant scope for improvement.

Factors responsible for the low average yields include:

- Limited availability of quality seed materials and agronomic inputs like fertilisers, herbicides and irrigation: For example, an unethical black market for oil palm seedlings exists, and there is some difficulty in obtaining highly improved seedlings, such as NIFOR’s Tenera variety.

- Most small and medium-sized farmers use rudimentary manual techniques for cultivation and harvesting activities. Consequently, there is scope for efficiency gains with more affordable mechanisation.

Volatility of Raw Materials Supply

Processors of agricultural commodities have challenges with sourcing raw materials. These challenges are illustrated by the experience of a large-scale rice mill operator who faced difficulties sourcing sufficient rice paddy for his processing facility in Ebonyi State.

- Sources of rice paddy ranged from Taraba, Benue and Nasarawa states.

- Transporting rice paddy over such long distances incurs significant costs.

This is a major driver of low-capacity utilisation at mills.

Product Spoilage in Transit and Storage

Nigeria’s deteriorating infrastructure and lack of basic amenities, such as stable electricity, harm the supply chains of perishable agricultural commodities like tomatoes. Fresh tomatoes are grown mainly in northern Nigeria and sold in markets in the south. These tomatoes are conveyed in raffia baskets in open trucks, which results in significant spoilage, as the distances covered are quite substantial (for example, the distance from Kano to Lagos is 12 – 16 hours by road).

The impact of spoilage on the pricing of tomatoes is illustrated in the following schematic (a full truck load of 400 baskets of tomatoes is assumed).

Out of 400 baskets of tomatoes.

- The first 150 are sold at a premium

- The next 100 are sold at nearly a premium

- The next 100 are sold at a mid-range price

- The last 50 are sold at “salvage price”.

Tomato sellers mitigate the risk of spoilage by:

- Transporting half-ripe tomatoes, reducing the percentage of spoiled tomatoes

- Instead of using raffia baskets, plastic crates could be used to transport the tomatoes (DFID pioneered an initiative to reduce spoilage by encouraging the use of plastic crates).

Female Participation in Agriculture

Women contribute significantly to agricultural activities. Despite this, men are usually considered the leading actors in agriculture (for cultural and other reasons) and tend to be the primary beneficiaries of agricultural support programs. Rural women, in most cases, are unable to acquire land or purchase/ register equipment in their own names. They cannot present certificates of occupancy (which are usually required by commercial banks for loans). Women often end up working as labourers for their husbands, performing much of the physical labour on the farm and receiving few benefits. For example, a census of rice harvesters in the Adani area of Enugu state showed that most were women (Achike, 2008). Despite this, most of the surveyed rice harvesting machinery was not owned by women.

- Women’s cooperatives have not been successful in addressing the challenge of increasing female participation in agriculture. Still, support is needed to promote changes, such as the cultural acceptance of female ownership of land/ agricultural equipment.

- Extensive education and encouragement are needed to drive cultural change, and this should be the focus of agricultural extension providers.

Upgrading a node in the value chain typically leads to the adoption of new technology, often resulting in women being displaced by men. This is a serious issue, given that women make significant contributions to rural agriculture.

Participation in urban agriculture is more balanced between the sexes, and urban farming responds more effectively to new technology than rural agriculture. However, urban agriculture tends to be temporary and can only be sustainable/beneficial in the long term if incorporated into urban planning.

Gender-related issues, such as those related to financial inclusion and technology adoption, are less pronounced with aggregators. In marketing and distribution, large-scale players are usually men, while women are typically small-scale players. Poultry farming is better organised and involves more female participation, and tends to be more urban.

Inadequate Funding for Research and Development

Nigeria has several agricultural research institutes, including the Nigerian Institute for Oil Palm Research in Benin, the National Root Crops Research Institute in Umudike, the National Cereals Research Institute in Badegi, and the National Horticultural Research Institute in Ibadan. These research institutes have contributed significantly to agricultural development in Nigeria in the past (for example, NIFOR was established in 1939 by the British, and a lot of the foundational work on oil palm research for the British Empire was carried out there).

Unfortunately, these institutions are not adequately funded. For example, the proposed total funding allocated to NIFOR in 2021 was ₦2.441 billion. (around $6,117,794.49) (Ekott, 2020). This amount included all funding for salaries, operating expenses, capital expenditures, and research, leaving minimal funds for research. In contrast, research and development in the Malaysian palm oil industry are driven by the Malaysian Palm Oil Board (MPOB). MPOB is partly funded by a research assessment levied on the volume of palm oil and palm kernel oil produced. This serves as a dedicated fund for research, development, and other support activities in Malaysia’s oil palm industry, which is well-funded. The estimated research assessment for 2021 was around $70 million (FAS USDA, 2023).

In addition, there is often a missing link between government research and private sector adoption. An example of this is a mechanical rice thresher developed by NCRI, Badegi, with the capacity for 3,000 kg of rice seeds per day, which is yet to be rolled out commercially.

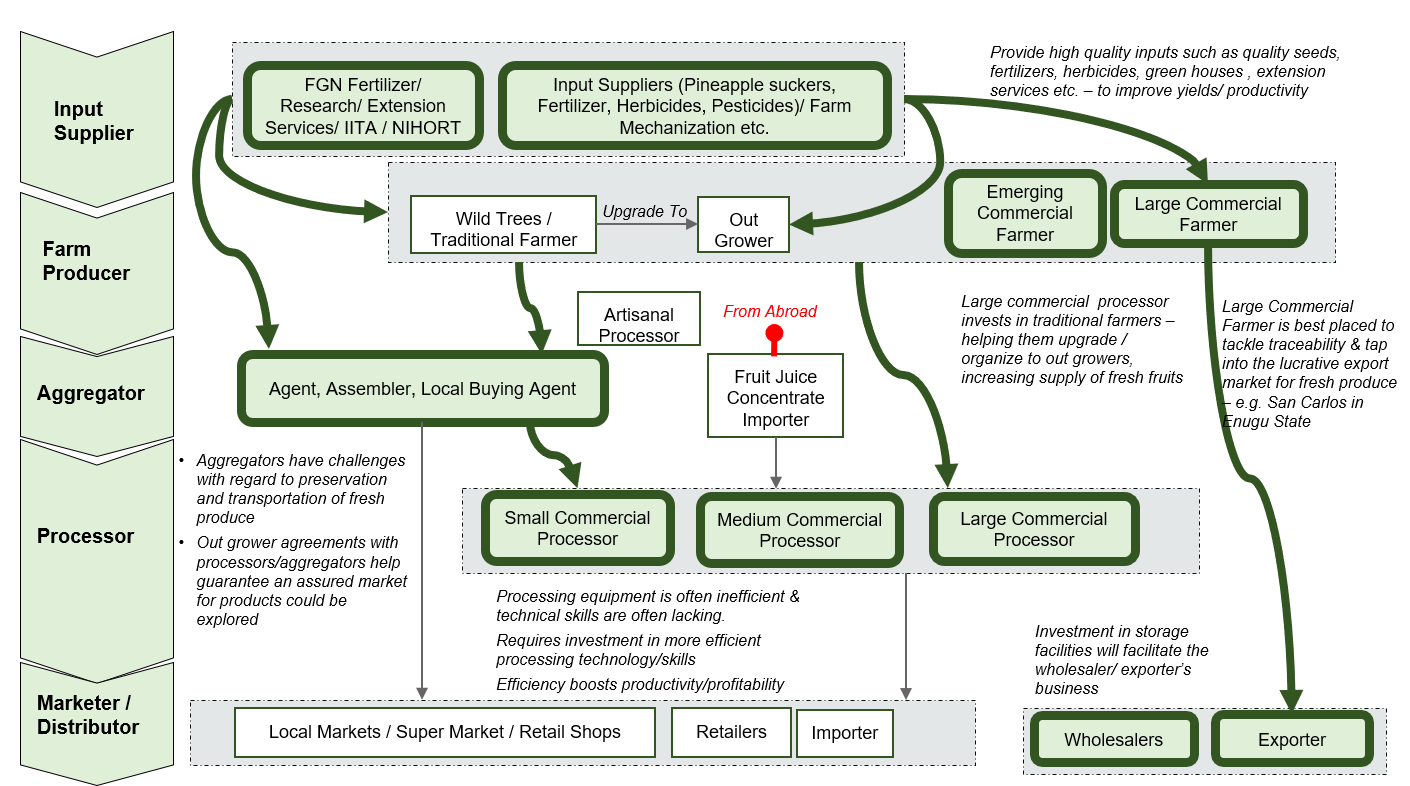

Improving agricultural outcomes in Nigeria is best accomplished by understanding the key constraints to growth in agricultural value chains and removing these constraints. This is illustrated and summarised in the following chart (which identifies the key leverage nodes and actors with potential for large impact in the horticulture value chain). Future articles will address the challenges of improving the key constraints to growth in agricultural value chains.

Figure 10: Key Leverage Nodes and Actors with Potential for Large Impact (Horticulture Value Chain)

References

As in linked texts